Roy’s critical stance on realism encompasses both her commitment to engage with contemporary history and her questioning of literature’s ability to do justice to suffering.

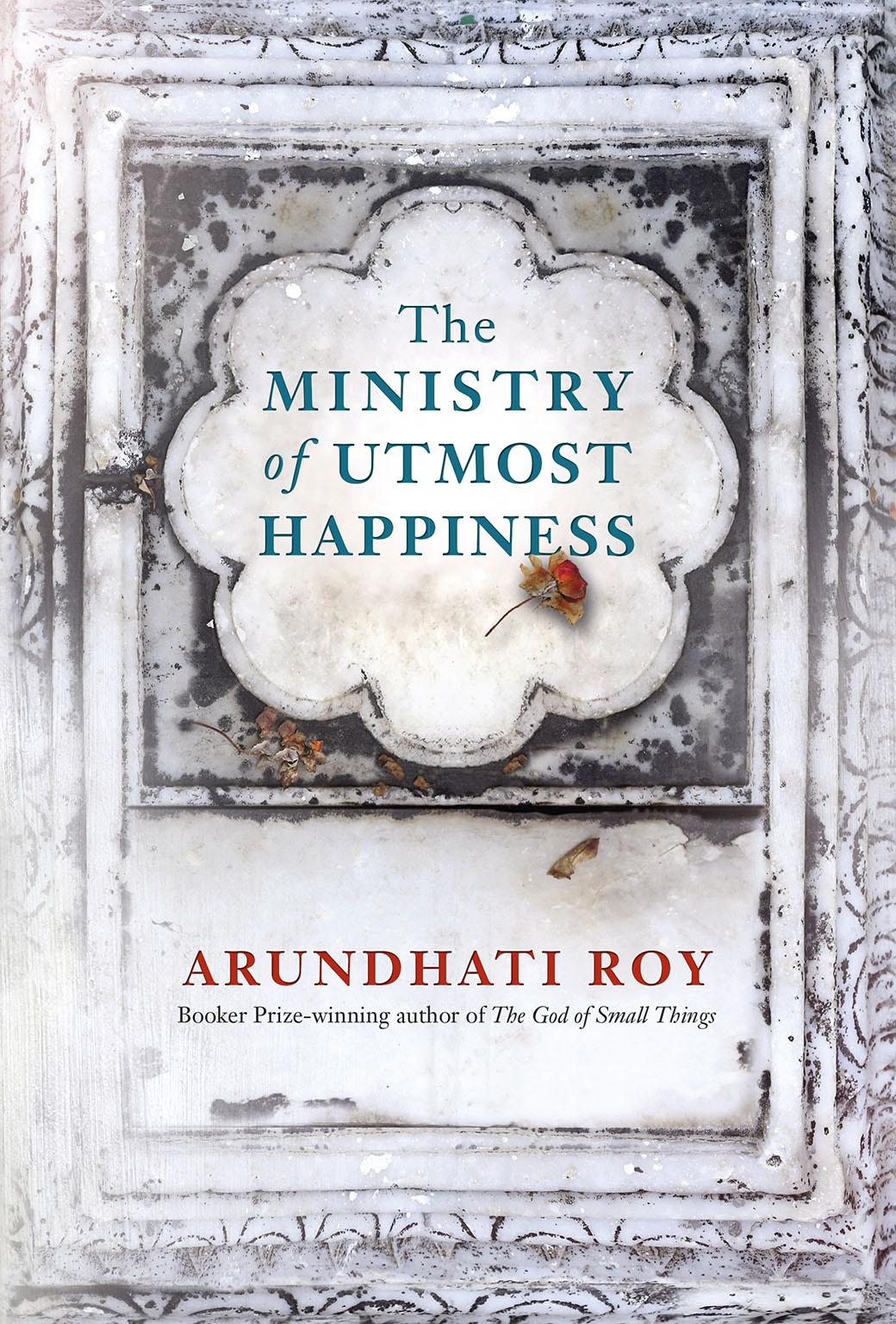

Rather than endorsing a concept of realism understood as transparent, documentary representation of reality, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness proposes a contradictory and digressive poetics whereby fictional and non-fictional elements coexist. This article reassesses the opposition between fictional and non-fictional writing by addressing Roy’s second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Arundhati Roy’s non-fictional writing has been interpreted as the epitome of an emerging “realist impulse” at the heart of postcolonial literature since 2000, and a move away from the reflexive and metaphorical style of her first novel, The God of Small Things.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)